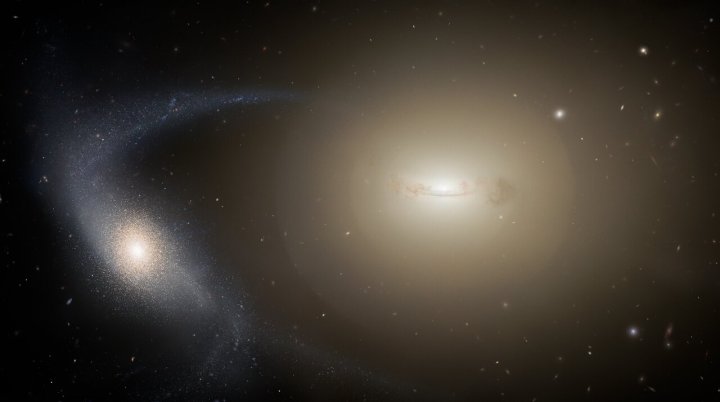

Galaxies come in many different shapes and sizes, including those considerably smaller than our Milky Way. These smaller galaxies, called dwarf galaxies, can have as few as 1,000 stars, compared to the several hundred billion in our galaxy. And when these dwarf galaxies age and begin to erode away, they can transform into an even smaller and more dense shape, called an ultra-compact dwarf galaxy.

The Gemini North telescope has recently been studying more than 100 of these eroding dwarf galaxies, seeing how they lose their outer stars and gas to become ultra-compact dwarf galaxies or UCDs.

“Our results provide the most complete picture of the origin of this mysterious class of galaxy that was discovered nearly 25 years ago,” said one of the researchers, NOIRLab astronomer Eric Peng in a statement. “Here we show that 106 small galaxies in the Virgo cluster have sizes between normal dwarf galaxies and UCDs, revealing a continuum that fills the ‘size gap’ between star clusters and galaxies.”

While astronomers did predict that dwarf galaxies could become UCDs, they hadn’t observed many cases of one transforming into the other. So this study looked for these “missing links” to see how this transition occurred. They found that these in-between galaxies were most often located near larger galaxies, which stripped away stars and gas from the small dwarf galaxies to leave a UCD behind.

“Once we analyzed the Gemini observations and eliminated all the background contamination, we could see that these transition galaxies existed almost exclusively near the largest galaxies. We immediately knew that environmental transformation had to be important,” explained lead author Kaixiang Wang of Peking University.

These objects were spotted using data from sky surveys, which was followed up using observations from Gemini North. That allowed the researchers to pick out the small dwarf galaxies from the many background galaxies visible in the sky.

“It’s exciting that we can finally see this transformation in action,” said Peng. “It tells us that many of these UCDs are visible fossil remnants of ancient dwarf galaxies in galaxy clusters, and our results suggest that there are likely many more low-mass remnants to be found.”

The research is published in the journal Nature.

Editors' Recommendations

- Biggest stellar black hole to date discovered in our galaxy

- Astronomers discover extremely hot exoplanet with ‘lava hemisphere’

- This peculiar galaxy has two supermassive black holes at its heart

- Spiral galaxy caught in the act as it’s about to eat its dwarf galaxy neighbor

- Zoom into stunning James Webb image to see a galaxy formed 13.4 billion years ago