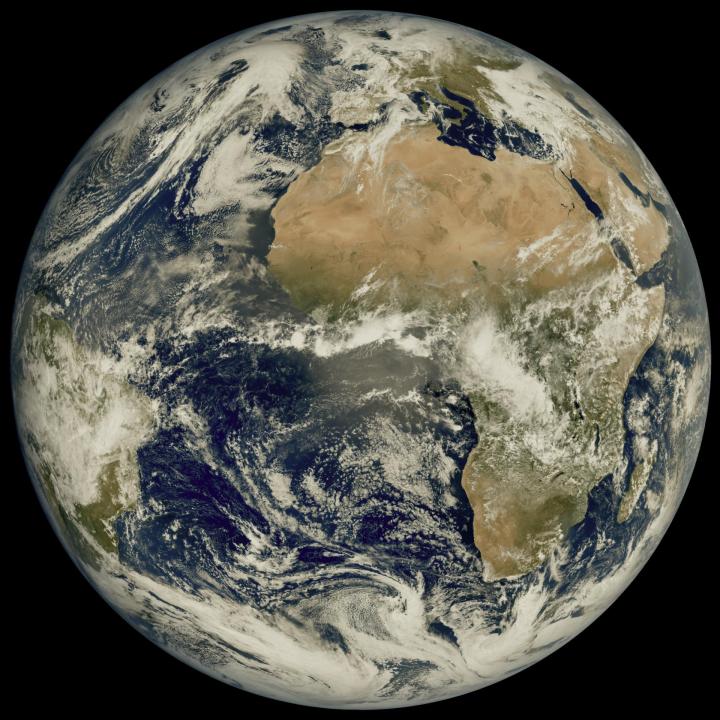

A recently launched weather satellite has sent back its first image of Earth, showing our planet in gorgeous detail. The European Meteosat Third Generation Imager-1 was launched in December of last year with the aim of monitoring weather conditions across Europe and Africa, and it took this image from its location 22,000 miles above the Earth’s surface.

The image was taken using the high-resolution Flexible Combined Imager instrument in March 2023, showing the areas of cloud and clear skies that can be seen over the Atlantic Ocean, as well as the European and African land masses.

The instruments on the Meteosat (MTG) are of a higher resolution than previous tools, as it is the first of a new generation of European weather satellites. This higher resolution allows weather features like clouds to be tracked more accurately, while also offering a view of how weather systems move across this part of the globe.

That will help with weather forecasting and dealing with extreme weather conditions such as hurricanes, according to the MTG team. “This remarkable image gives us great confidence in our expectation that the MTG system will herald a new era in the forecasting of severe weather events,” said Phil Evans, director general of the European weather-monitoring satellite agency Eumetsat, in a statement.

“It might sound odd to be so excited about a cloudy day in most of Europe. But the level of detail seen for the clouds in this image is extraordinarily important to weather forecasters. That additional detail from the higher-resolution imagery, coupled with the fact that images will be produced more frequently, means forecasters will be able to more accurately and rapidly detect and predict severe weather events,” the team said.

The team says that data from the satellite will also help international weather forecasting and climate change monitoring. “The high-resolution and frequent repeat cycle of the Flexible Combined Imager will greatly help the World Meteorological Organization community to improve forecasts of severe weather, long-term climate monitoring, marine applications, agricultural meteorology, and will make an important contribution to the Early Warnings For All Initiative, in particular on the African continent,” said Natalia Donoho of the World Meteorological Organization.