Astronomers often share news about strange and exotic exoplanets, like one that is shaped like a football or another that has metallic rain. But far-off stars can be strange as well, as one recent piece of research points out. An enormous new type of star, which researchers are calling a “heartbreak” star, has gigantic waves on its surface that are three time the size of our sun.

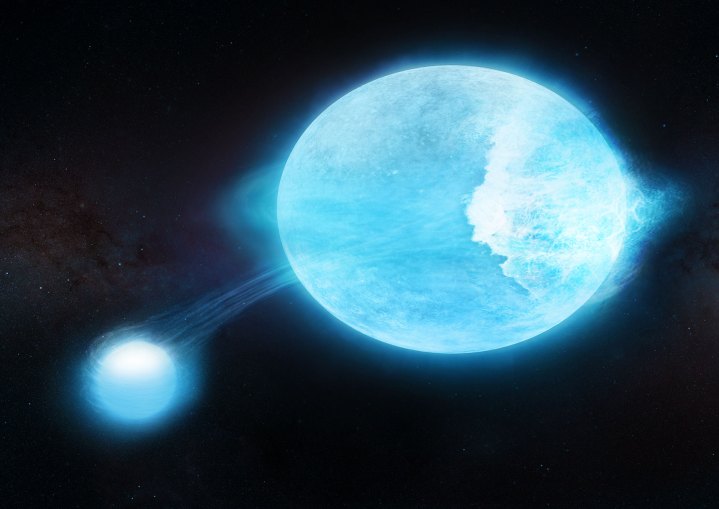

The star, officially called MACHO 80.7443.1718, gives off regular pulses of brightness, making it similar to a known type of star called a heartbeat star. Stars like this are typically one of a pair, which orbit each other in an elongated, oval-shaped orbit. When the two stars come close to each other, their gravitational forces pull at each other, creating waves on their surfaces, similar to how the moon causes tides on Earth. But this particular star is an extreme version of the phenomenon, with brightness that varies by 200 times as much as a typical example.

This star is large, at 35 times the mass of the sun, and its much smaller companion creates the huge waves that cause the pulses of brightness. These waves reach up to a fifth of the star’s radius, or 2.7 million miles in height, which is about the same height as three of our sun.

“Each crash of the star’s towering tidal waves releases enough energy to disintegrate our entire planet several hundred times over,” said lead researcher Morgan MacLeod of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian in a statement. “These are really big waves.”

The creation and movement of the waves was simulated using a computer model, which showed that the waves swell upwards before crashing over, just like ocean waves. That releases large amounts of energy and results in spray and bubbles, creating a stellar atmosphere and affecting the spin on the star’s surface. This happens around once per month when the two stars pass each other.

“This heartbreak star could just be the first of a growing class of astronomical objects,” MacLeod says. “We’re already planning a search for more heartbreak stars, looking for the glowing atmospheres flung off by their breaking waves.”

The research is published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Editors' Recommendations

- Scientists investigate star formation in the famous Whirlpool Galaxy

- James Webb observes merging stars creating heavy elements

- Hubble measures the mass of a lonely dead star for the first time

- China’s Tiangong space station has a new three-person crew

- Hubble Space Telescope captures the earliest stage of star formation