For more than a decade, NASA’s Near-Earth Object Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (NEOWISE) mission has been searching the sky for near-Earth objects. Using its infrared vision, the spacecraft, which sits in orbit above Earth’s surface, has looked out for asteroids and comets throughout the solar system and has been used to identify those that could come close to Earth.

You might recognize the name because it was used for one of the mission’s discoveries, comet NEOWISE, which was the brightest comet in over 20 years when it zipped past Earth in 2020.

But the NEOWISE mission will soon be coming to an end, as the spacecraft will drop into Earth’s atmosphere and burn up. The team is preparing for this end to come early next year and is getting the last science they can from the spacecraft before it is no longer usable.

A mission can come to an end in several ways. If a spacecraft is reliant on solar power, as many are, then it may peter out as its panels lose efficacy. That’s what happened to the InSight lander on Mars, as its solar panels were covered in dust carried by winds that built up over time until it eventually couldn’t generate enough power to keep operating. Or a spacecraft that’s in orbit might run out of propellant, so it’s no longer able to orient itself and return information to Earth, as happened with the Kepler Space Telescope.

Sometimes, a mission is no longer necessary because it’s been replaced by newer and better technology. The Spitzer Space Telescope, for example, was a pioneer in the field of infrared astronomy, but with the launch of the more powerful James Webb Space Telescope on the horizon, it was no longer necessary.

But what happens to a spacecraft once its mission is over? How do you go about turning these things off? We spoke to members of the team for NEOWISE, a NASA mission that is preparing to go offline next year, to find out.

A grand end

Some spacecraft can be left to safely drift off into space as long as there is no chance of them hitting anything or causing any damage. That’s what happened to Spitzer, which will gently float away from the planet for the next 50 or so years as it orbits the sun and trails the Earth.

Spacecraft in orbit around planets, however, need to be carefully disposed of. When the Cassini mission to Saturn came to an end, it was dramatically plunged into the planet’s atmosphere, or deorbited, so that it would deliberately break up and be destroyed. That ensured there was no chance it could contaminate any of the moons of Saturn, which could be potentially habitable. The final descent also allowed a bunch of incredible new research into Saturn’s atmosphere to be made.

The NEOWISE spacecraft is orbiting Earth, so it, too, needs to be safely disposed of. The concerns are that the spacecraft shouldn’t be left to become space debris, an increasing problem in some orbits and that its deorbiting shouldn’t pose a danger to anyone on the ground.

That last point isn’t a given. There have been cases where pieces of deorbited craft have landed on the ground, such as with the Skylab space station, which fell from orbit in 1979, pieces of which landed in Australia.

Today, missions have to plan for how they’ll be deorbited before they are even launched.

A specialized team at JPL (NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory) analyzes what breakups will look like based on factors about the spacecraft, like its mass and velocity. That makes the effects of a deorbiting predictable.

“There’s very minimal chance, if any, that any debris will come down and injure someone,” said Joseph Hunt, project manager for NEOWISE at JPL. The spacecraft’s orbit will drop, making it burn up in Earth’s atmosphere early next year.

“We want to end this mission gracefully,” Hunt said.

Why NEOWISE is ending

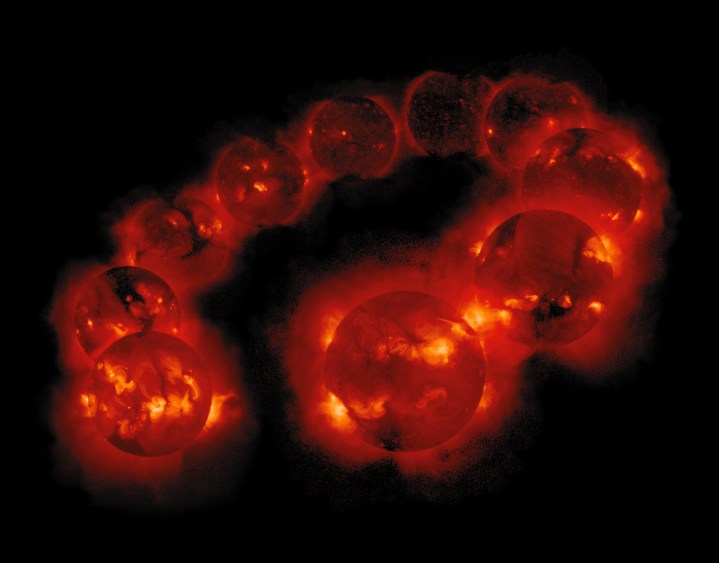

NEOWISE isn’t running out of fuel — it doesn’t have any propellant on board — nor has it become an antique. But the activity of the sun is forcing its demise.

The spacecraft sits in a low-Earth orbit, around 300 miles from the planet’s surface, and that means it is affected by the planet’s atmosphere.

“The sun is constantly spewing out charged particles and radiation at multiple wavelengths. What happens when it hits the Earth’s atmosphere is that it can cause it to puff up. It can cause the atmosphere to extend a bit beyond its normal altitude,” explained Amy Mainzer, Principal Investigator of the NEOWISE mission.

The sun operates on a roughly 11-year cycle of activity, sometimes more active and sometimes less. NEOWISE got lucky and began its extended mission during a period called solar minimum, when the sun’s activity was low. And it has been a particularly quiet solar minimum, so the atmosphere has been less extended than usual. That has all allowed the spacecraft to survive for longer.

“It really is ultimately up to Mother Nature.”

But this low solar activity doesn’t last forever, and we are now entering a period of increased solar activity, with more radiation from events like solar flares affecting the atmosphere. And that spells the end for the spacecraft.

“You would think we’re in space, up at around 500 kilometers in orbit, you would think that is totally free of atmosphere. But not quite,” said Mainzer. “There’s a tiny little bit left, and that is enough to cause drag forces that pull on the spacecraft and eventually pull it into the atmosphere.”

With no onboard propulsion, the spacecraft can’t push back or move to another orbit. It can only rotate in place, so it’s “a battle we can’t win,” Mainzer said.

Knowing the end is coming, the NEOWISE team sets a date when they are comfortable with ending the mission. The problem is that as the drag from the atmosphere increases, it becomes harder and harder to control the spacecraft, and the ability to control it drops drastically and quickly.

“The laws of physics, in the end, always dictate what happens,” said Mainzer. “It really is ultimately up to Mother Nature.”

A second life

NEOWISE has been in operation since 2013, so it’s had a good run of 11 years of operation. But in fact, it’s already on its second life. That’s because it was previously an entirely different mission called WISE.

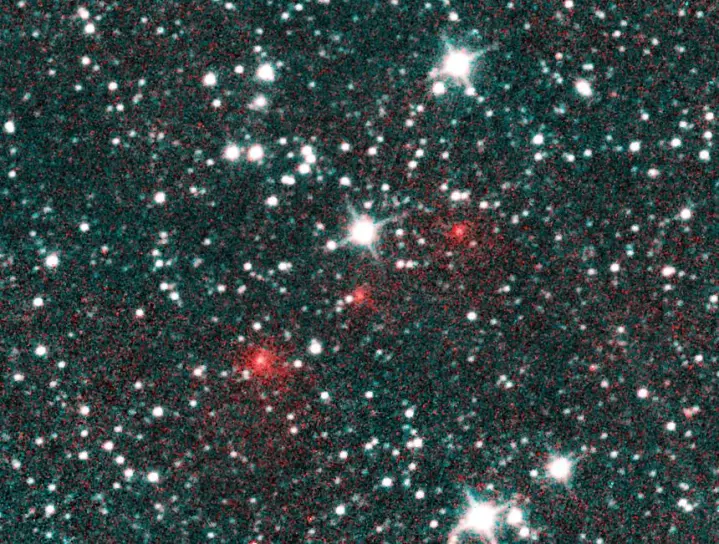

WISE, or Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, was launched in 2009 and was designed to study objects within the solar system and beyond, including the Milky Way and more distant galaxies. In its time, the mission discovered thousands of small objects called minor planets, as well as discovering many star clusters. It also discovered the first Earth Trojan, an asteroid that shares an orbit with Earth.

The mission used infrared detectors, which must be chilled to very cold temperatures to work. The original temperature was just 8 Kelvin, which was achieved using solid hydrogen as a coolant.

But coolant gets used up. By 2011, its mission was complete, and its coolant was gone, so the spacecraft was put into hibernation. “I thought that was the end of the story,” Mainzer said.

But later, in 2013, NASA was interested in using a spacecraft to search for near-Earth objects, and the team realized that the WISE spacecraft might be able to do that. It was reactivated and cooled to its new operating temperature over several months. The spacecraft stabilized at 75 Kelvin, “which for a cryogenic scientist is like a warm summer day,” Mainzer said.

At this warmer temperature, two of its four channels wouldn’t work correctly, but the remaining two channels could still be used for science. Over the last decade, the spacecraft has surveyed the sky, looking for — and finding — thousands of near-Earth objects using millions of infrared measurements.

“It’s been an incredible cosmic jackpot to get this much time out of the spacecraft,” Mainzer said. “It wasn’t supposed to happen.”

Saying goodbye

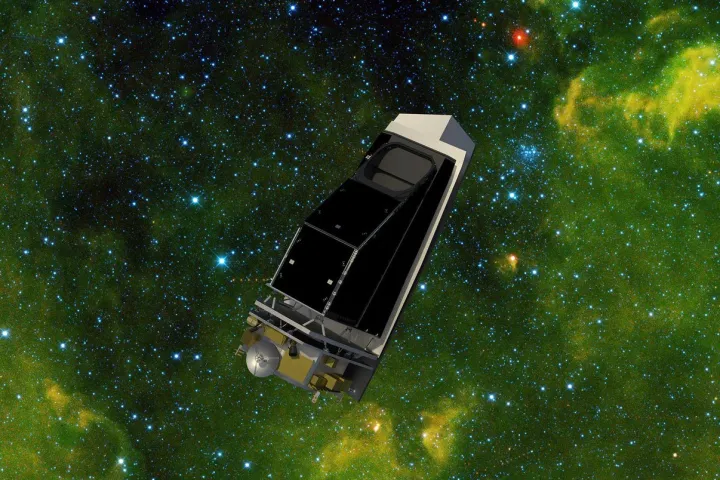

Although NEOWISE is now coming to an end, it won’t be long before it gets a successor. The NEO Surveyor mission, which is working toward a 2027 launch, is also an infrared spacecraft that was inspired by the success of NEOWISE. It will have the benefits of improvements in IR detectors, which have become much more powerful in the last decades thanks in part to technology driven by cell phone cameras.

Mainzer will be the PI for NEO Surveyor as well, and is already busy overseeing the arrival of hardware for the spacecraft ahead of integration.

Before that launch, though, the team is still working on closing out the NEOWISE mission and all that it involves. NASA doesn’t like to showcase the end of missions, Hunt said, preferring to focus on new launches or newly acquired data. But they want to ensure the mission ends with appropriate fanfare, so that involves talking to the media and celebrating the mission’s accomplishments, as well as preparing reports and internal documents.

Not to mention, the spacecraft is still doing science right up until the last possible minute, so mission operations need to be maintained. “You never know with these missions, when the greatest piece of science possible could be made public, or the greatest observation could happen,” Hunt said. “It could be the day before we turn it off!”

When the final day of the mission comes, it will be a bittersweet experience for the team. NEOWISE has achieved far more within its multiple lifetimes than was ever expected, but it’ll still be sad to see it go.

“In some ways, these spacecraft are little extensions of yourself. It’s like your eyes in the sky. You can see what it sees,” Mainzer said. But, she added, what drives her to do the next mission is how much fun she and the team had with NEOWISE. Now it’s on to the next adventure, she said: “Let’s go see some more good stuff!”

Editors' Recommendations

- Watch how NASA plans to land a car-sized drone on Titan

- NASA addresses the crack in the hatch of the Crew-8 spacecraft

- Watch NASA test its next-gen spacesuit for ISS spacewalks

- NASA readies Starliner spacecraft for first crewed flight to ISS

- Astrobotic reveals how things will end for its troubled Peregrine spacecraft