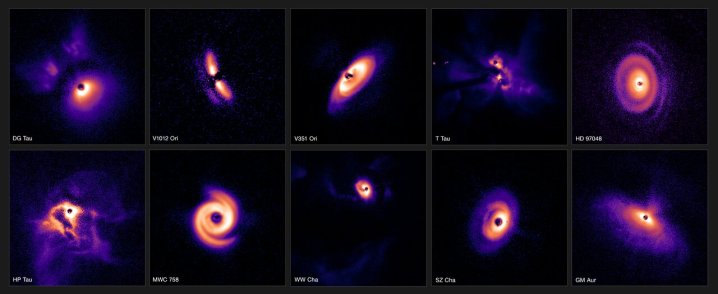

Astronomers have used the Very Large Telescope to peer into the disks of matter from which exoplanets form, looking at more than 80 young stars to see which may have planets forming around them. This is the largest study to date on these planet-forming disks, which are often found within the same huge clouds of dust and gas that stars form within.

A total of 86 young stars were studied in three regions known to host star formation: Taurus and Chamaeleon I, each located around 600 light-years away, and Orion, a famous stellar nursery located around 1,600 light-years away. The researchers took images of the disks around the stars, looking at their structures for clues about how different types of planets can form.

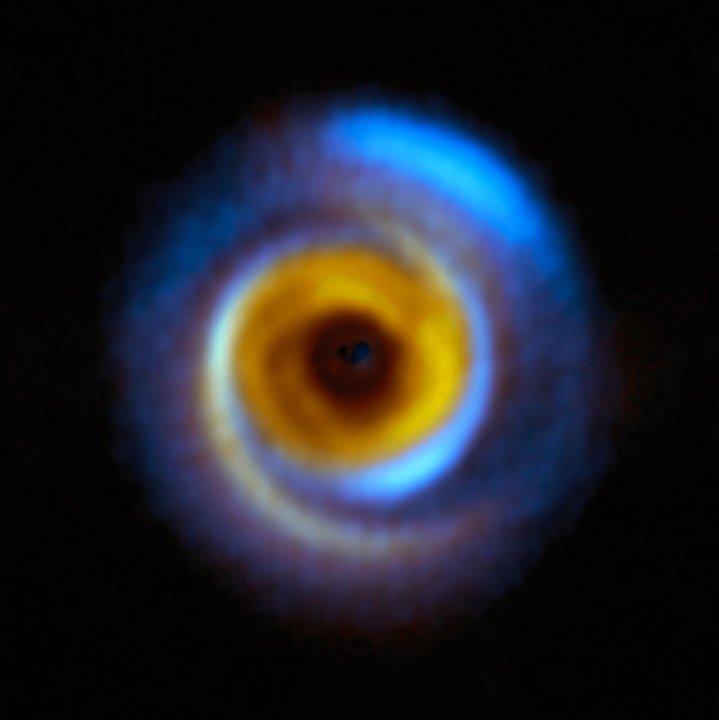

“Some of these discs show huge spiral arms, presumably driven by the intricate ballet of orbiting planets,” said one of the researchers, Christian Ginski of the University of Galway, Ireland, in a statement. “Others show rings and large cavities carved out by forming planets, while yet others seem smooth and almost dormant among all this bustle of activity,” added another researcher, Antonio Garufi of the Arcetri Astrophysical Observatory, Italian National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF).

The apparent clumpiness of some disks suggests that massive planets may already be forming within them. Some of the findings gave clues to how these planets develop: In Orion, for example, the researchers found that when there were two or more stars in a group, they were less likely to have a large planet-forming disk.

The researchers were able to see the disks using a combination of tools, such as the Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch instrument (SPHERE) and X-shooter instruments on the Very Large Telescope and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA).

“This is really a shift in our field of study,” said Ginski. “We’ve gone from the intense study of individual star systems to this huge overview of entire star-forming regions.”

The research is published in three papers in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.